Some foods just don’t need anything other than a little salt and pepper. A great steak comes to mind. On the other hand, some meats love swimming in sauces. Like pork ribs. Other meats are not very flavorful on their own, and are a blank canvas that is easily painted with herbs, spices, and flavorful liquids. There are several ways to amp up the flavors of foods before cooking.

Seasoning

When chefs speak of seasoning a dish, they are usually not referring to adding herbs and spices. They are usually talking about salt and pepper. Period. And most chefs think that these two basic additives are absolutely positively essential. Salt is an excellent flavor enhancer because it actually opens up your taste buds and this really wakes up the flavor of meat and vegetables. It also helps meat retain water. If your diet requires low salt, go easy on it, but if you can handle a little, don’t skip a little “Dalmatian rub”, just plain salt and pepper, on almost anything. Click here to read more about salt and the different types of salt.

When the rest of us speak of seasoning, we usually mean salt and pepper and all the other flavorings. Spice blends, commonly called dry rubs, and wet rubs, which are spice blends mixed with water or oil are a great way to amp it up to 11. Pesto is a classic wet rub made with an oil base.

Dry rubs are a mix of spices and dried herbs and they are rubbed into the meat before cooking. They come in a wide range of flavors. There are barbecue rubs, chili powder (yes chili powder is a spice blend), curries, jerk seasoning, sate, Old Bay, and many more. Find some rub recipes you like, make a big batch, and put them in a large spice shaker with a lid. If it clumps or cakes, you can do what waitresses in diners have been doing forever: Dry some rice in the oven or a pan and add it to the jar to absorb the moisture.

You can buy pre-mixed rubs, but they are easy to make yourself, and a lot cheaper since most commercial rubs are loaded with salt. Every good barbecue cook should have a few signature house rubs to brag on. Just steal my recipes. Click here to see a list of them with links to the recipes. Then experiment with variations. But remember, you cannot judge a rub raw. It tastes very very different after cooking. The juices of the meat mix with the herbs and spices, melt them, and they undergo chemical reactions catalyzed by the heat of the fire. A rub may taste too hot when raw, but keep in mind there will be a bite sized piece of food underneath it diluting it. You may hate rosemary, but you’ll never notice it in the blend, after mixing with juices, after cooking, and in with a mouthful of pork. As always, I recommend you make my recipes unaltered the first time, and after you cook with it you can then alter it to your tastes.

The five Ss

A good rub is like a good orchestra, it has a range of instruments to play all the notes in harmony. They are:

Sugar. Sweetness is a common addition because it is a flavor enhancer, it helps browning, and with crust formation. More on sugar below.

Savory. There is an herb named savory, and in common language we speak of savory as being a pleasant smell or taste, but in the culinary arts, savory flavors come from amino acids called glutamates, green herbs, some spices, garlic, and other flavorings.

Spices and herbs. Not all of them work on all foods, but the spice rack is full of great flavors. Paprika is often included, not so much for flavor as for color. Click here to read more about spices and herbs.

Spicy. Hot pepper sensations, often called spicy flavors, are often in rubs because they add excitement, but go easy, not everyone likes it as hot as you do. Black pepper is common, so are ground hot peppers such as cayenne or chipotle. Ginger, horseradish, and mustard powder also fit in this category. Click here to read more about chiles.

Salt. Almost all bottled commercial rubs have salt. This is pretty much a standard. As we have discussed elsewhere, salt is important because it penetrates deep, because it amplifies flavor, and because it helps meat retain moisture. But as I explain below, if you make rubs at home, you shuld leave out the salt.

No salt in homemade rubs

Salt penetrates, so the amount we apply depends on the weight of the meat. All the other ingredients in a rub are huge molecules that rarely go beyond the pores and cracks in the surface, not more than 1/8″ deep. So spices and herbs are a surface treatment just like sauces so the amount we apply depends on the per square inches of surface.

Applying the salt separately and in advance is a very important technique called dry brining. Dry brining is simply salting thick cuts the day before cooking and thin cuts an hour or two before. Adding salt in advance is good for the meat because it dissolves on the wet surface of meat and it penetrates deep. You should click this link and read more about dry brining.

Adding spices in advance does little to benefit the meat below the surface because they cannot penetrate. Read more about why rubs and marinades don’t penetrate in my article on marinating.

You need more salt on a pork shoulder than on pork ribs because a shoulder is thicker and heavier. You need more salt on rib roast than a ribeye steak, and more on a ribeye steak than on skirt steak. You need more salt on chicken breasts than on thighs or drums. You need more salt on the thick part of a leg of lamb than on the thin part. You don’t need more spices on any of these because they don’t penetrate. Keeping salt and the other Ss separate lets you apply the right amount of each.

There are other good reasons why our rub recipes don’t have salt:

- You do not need any salt at all on cured meats like a ham, bacon, or corned beef, but you might want sugar, savory, spices, and spicy.

- Nowadays almost all turkeys and many ribs, pork loins, chickens, and other meats are injected with a salt solution at the processor. This helps meat retain moisture, and adds weight which means profit. This trend is not going away. Many readers tell me they cannot find ribs that have not been pumped. Meat that is labeled “enhanced” or “flavor enhanced” or “self-basting” or “basted” has been injected with a brine at the packing plant. Kosher meat has also been treated with salt at the plant.

- Some people like more or less salt than others. By keeping it separate you can tailor saltiness to your taste. On more than one occason I have been sent rubs to test and after applying them discovered to my dismay, that the meat was way to salty. Why? Because I just didn’t know how much salt was in the rub and I couldn’t control the amount of salt applied.

- Some people are on salt restricted diets, although when you do the math, the salt used in preparing meat, up to 1/2 teaspoon of Morton Coarse Kosher Salt per pound, is way below your limit.

- You might want to brine the meat and then you will have a meal that is too salty.

- Some rubs are mixed with oil, and salt will not dissolve in oil. If you apply salt first, the water in the meat will pull it in. Then the oil won’t interfere.

- Leaving salt out of the mix also gives you room to add a finishing salt just before serving. A sprinkle of large grain salt on a steak as soon as it comes off the grill give it real pop. In some cases, such as Memphis style “dry” ribs with no sauce, you might want to apply a layer after cooking before serving. If there is no salt in the rub there is no risk of oversalting.

You can add the salt at the same time as the spices. No harm, no foul. It will still penetrate, maybe not as deep, but it will travel when it gets wet and warm. But if you can get it on in advance, you give it a head start. Injecting is also a good idea. You should consider injecting thick meats, especially beef brisket and turkey breast (if they are not already injected).

Almost all commercial rubs have salt in them. Sometimes half the blend is salt. That’s because having salt and spices in one jar is convenient. Besides, most rub manufacturers haven’t figured out the science and if they took the salt out they would be so expensive people wouldn’t buy them.

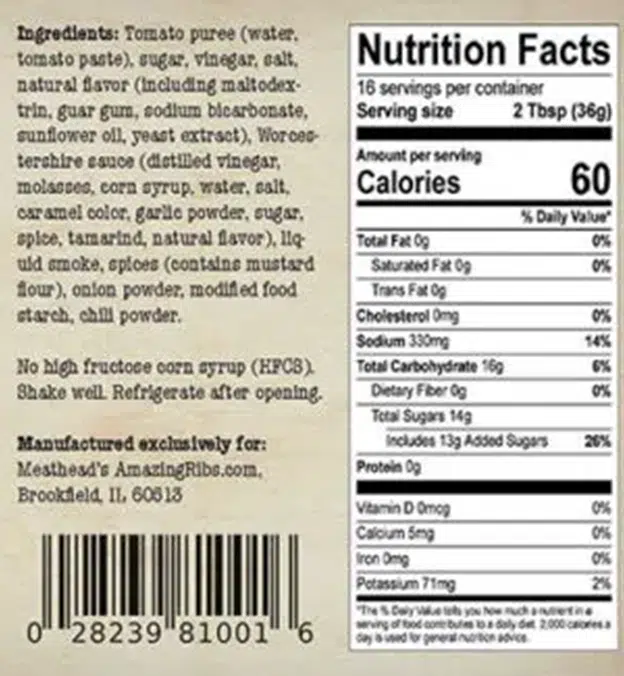

So salt, rub, and sauce should be three separate applications. Applying the salt, the rub, and the sauce separately is like controlling the gas pedal, break, and clutch. Work them in harmony but separately.

Keeping the salt in one hand and the rub in the other gives you a lot more freedom and control. Remember, you can always add salt, but you can’t take it away.

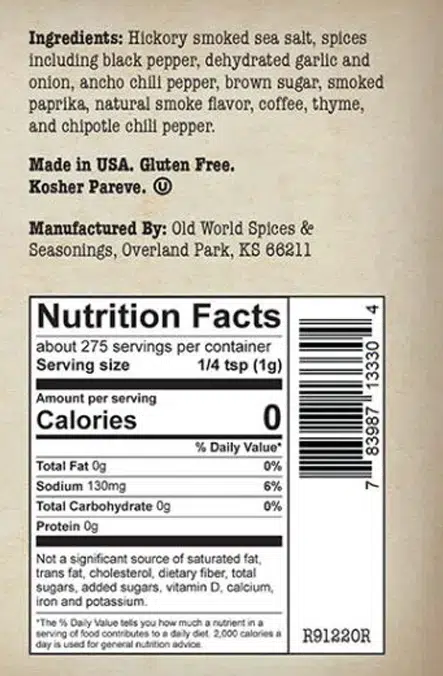

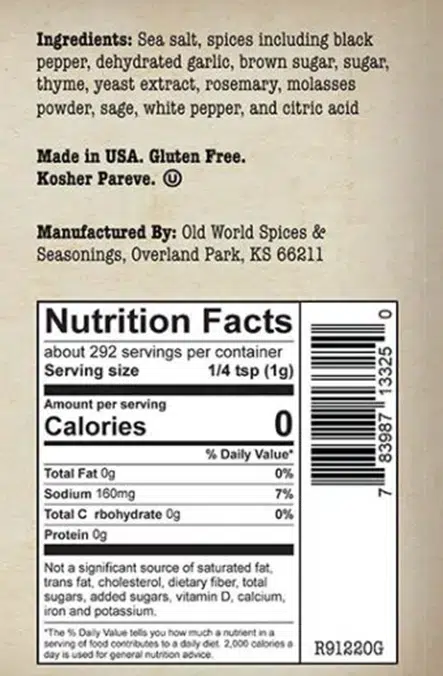

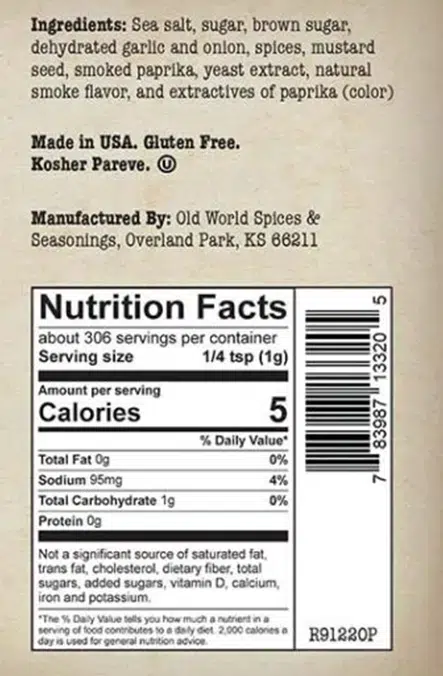

Why there is salt in our rubs?

When you make rubs at home from our recipes, we recommend you do not add salt because salt penetrates and none of the other spices and herbs do, so thick cuts need more salt. We put salt in these bottled rubs because all commercial rubs have salt and consumers expect it. Without salt buyers would wonder why their food needs salt. There’s not enough room on the label to explain why we left out salt as we have above. Besides, without salt the price would be outlandish. You can still use them as a dry brine, just sprinkle the rub on well in advance to give the salt time to penetrate. For very thick cuts of meat, we recommend adding a bit more salt. Please note that we have gone easy on the salt. It appears first in the ingredients list because the order is dictated by law by weight, not volume, and salt is a heavy rock. It weighs a lot more than pepper, paprika, and all other spices.

Sugar in rubs

I often get asked about the sugar in rubs and other recipes. Is it necessary? Can I use less? Can I use a sugar substitute?

Sugar is a common addition to rubs because it is a flavor enhancer, it helps browning, it helps with crust formation, and it balances bitterness and acidity.

Sugar substitutes may work fine in sweetening your tea and in some sauces, but not in spice blends. That’s because the chemical properties of this colorless, odorless, crystal are unique and what happens to them on meat when heat applies is special.

Sugar plays a role in the Maillard reaction, the most important chemical reaction in cooking. The Maillard reaction is often oversimplified by calling it the browning reaction, but it is much more complex. It is the transformation of proteins, amino acids, and sugars into new compounds that are loaded with flavor. Think about how much more flavor there is in the crust of a beef roast than in the meat in the center. The bark on ribs, pulled pork, and brisket is also primarily due to this chemical powerhouse.

Another chemical reaction, caramelization, is important in cooking. During caramelization water is released from sugar and new compounds with buttery caramel-like flavors are formed. Different sugars caramelize at different temperatures and that is why some recipes call for more than one type of sugar.

Fructose (the sugar in fruits) 230°F

Sucrose (table sugar) 320°F

Glucose (the sugar in blood) 320°F

Lactose (the sugar in milk) 397°F

Sugar also is hygroscopic, meaning it attracts water. So when a rub with sugar is applied to meat, it pulls moisture to the surface where it dissolves the sugar and some of the other spices and their compounds and forms a slurry. Sugar and spices are too large to go past the tiny cracks and pores on the surface, so they remain there and cook, their chemistry changing with the heat. As the surface dries, the sugar and spice slurry meld with meat juices, fats, and protein to form bark. The more the sugar is cooked, the more its chemistry changes and the less sugar and sweetness remain.

Sugar is even more crucial in baking. Most importantly, it is the favorite food for yeasts, so sugar helps dough rise. That’s why I put a pinch in my pizza dough recipe. The Maillard reaction is also important in baking for the browning of crusts. Of course caramelization is crucial in making pastries. When making a cake, muffins, or cookies, sugar traps air when beaten with butter (creaming) making bubbles that capture gasses released by the leavener. The more tiny bubbles in your batter, the lighter the texture and finer the crumb. Sugar is also essential for thickening and stabilizing beaten egg whites, and holding moisture when cooked.

So let’s do some math. Our most popular rub, Meathead’s Memphis Dust is 60% sugar. Let’s say you apply 1 tablespoon per side on a slab of ribs, a total of 2 tablespoons or 6 teaspoons. So on a slab of ribs there are about 3.6 teaspoons of sugar. During cooking, some of it melts and drips off leaving, let’s say, 2.5 teaspoons. So if you eat half a slab you are getting 1.25 teaspoons of sugar.

If you use 1/4 cup (4 tablespoons) of Meathead’s Memphis Dust on a pork butt that’s about 2.4 tablespoons of sugar. After drip loss, let’s say there are 2 tablespoons left. From an 8 pound butt there will be about 6 pounds after shrinkage during cooking. If a serving is a generous 1/2 pound, there are 12 servings dividing those 2.4 tablespoons of sugar (about 7 teaspoons), or a bit more than 1/2 teaspoon per serving, all of it on the bark.

The glycemic load of each serving above is about 4, about the same as 8 ounces of skim milk. Compare that with a slice of white bread with a GL of 10.

Water or oil under the rub?

You can put a rub right on bare meat, or you can help it stick by moistening the meat with a little water, oil, or a slather of mustard, mayo, or ketchup. We hope that the spices and herbs will melt a bit, make a nice flavorful slurry that will become a major part of the desirable flavorful lovable bark when it is heated and dries out.

Here’s a little experiment I did. I put my two most popular rubs in oil and water. Meathead’s Memphis Dust, which is mostly spices, and Simon & Garfunkel Rub, which is mostly herbs. As you can see, they dissolved much better in water. Think of how well tea leaves infuse water.

My experience is that they make little or no difference in the final outcome. I also tried them in 40% vodka and they dissolved a little better than water, but alcohol can really mess with the structure of protein so I don’t recommend it.

Many cooks like to use a base of bottled mustard under their rub. Bottled mustard is a mix of powdered mustard with water, vinegar, and/or white wine, all mostly water. The amount of mustard powder is so small that by the time the water steams off and drips away, the mustard powder remaining is miniscule. If you want a mustard flavor, you will do much better by simply sprinkling it on the meat. Far more important is what is in the rub than under the rub. So use whatever you want.

Bloom your spices

Toasting many spices amplifies their flavors by releasing their oils and changing chemicals constructions through the maillard effect. So here’s a trick to take your rubs to the next level. Warm a frying pan over medium heat and pour in your spices. Stir or shake them often. Don’t let them sit still for more than 10 seconds or they can burn. It only takes about two minutes to bloom them. You’ll know when the fragrance jumps out at you.

Either pour them out of the hot pan immediately or else they will continue to cook and burn or, if you wish, make a wet rub by adding some oil, not a lot, just enough to make a paste, and turn the heat as low as possible and cook for another minute so the oil will pull out more of the flavor.

Applying a rub

To prevent contaminating your rub with uncooked meat juices, spoon out the proper amount before you start and seal the bottle for future use. Keep your powder dry.

There is a popular myth that you should not rub a rub, that you should sprinkle it on because rubbing it in cuts the surface and juices will run out.

Humbug. There is a reason they are called cuts of meat. Meat is muscle that has been cut to remove it from the bones, fat, and other muscles. The surface has already been in a knife fight and there are gazillions of muscle fibers that have been sliced open. There are also bazillions of microscopic ridges, valleys, cracks, crevices, pits, pockmarks, and pores in the surface. The surface is far from smooth. Rubbing a rub into the surface can’t hurt it one bit. It is not going to lose any more juice than if you just sprinkle it on. And rubbing might just help the meat hold onto the rub better.

To prevent cross-contamination, one hand sprinkles on the rub and the other hand does the rubbing. Don’t put the hand that is rubbing into the powder.

Skip the plastic wrap

After salting, the best arrangement is on a wire rack over a pan, no wrap. There is nothing about plastic wrap that forces salt or rub molecules into the meat. It is not some sort of vacuum or pressure system. Plastic wrap just gets stuck to the rub and pulls it off when we remove the plastic. Liquid also accumulates in the plastic and washes away some of the spices. If you are dry brining poultry, you actually want airflow around the meat to help desiccate the skin.

In the restaurant world you are required by law to cover or wrap the meat so juices won’t contaminate other foods like veggies. This makes sense, so be very careful if you leave raw meat uncoverd in the fridge. If you wish, a roasting pan with a rack and a dome will work just fine.

If there are odors in the fridge, if there is something really smelly in there, plastic wrap will help keep out the smell, but remember, plastic wrap does not prevent air from entering and exiting, so if there is one of Tony Soprano’s dead friends in your fridge, the smell can penetrate most plastic wraps.

Otherwise, just leave the meat nekkid on a rack in a pan on the bottom shelf of the fridge. If you feel safer wrapping, go ahead. It really won’t hurt much.

High quality websites are expensive to run. If you help us, we’ll pay you back bigtime with an ad-free experience and a lot of freebies!

Millions come to AmazingRibs.com every month for high quality tested recipes, tips on technique, science, mythbusting, product reviews, and inspiration. But it is expensive to run a website with more than 2,000 pages and we don’t have a big corporate partner to subsidize us.

Our most important source of sustenance is people who join our Pitmaster Club. But please don’t think of it as a donation. Members get MANY great benefits. We block all third-party ads, we give members free ebooks, magazines, interviews, webinars, more recipes, a monthly sweepstakes with prizes worth up to $2,000, discounts on products, and best of all a community of like-minded cooks free of flame wars. Click below to see all the benefits, take a free 30 day trial, and help keep this site alive.

Post comments and questions below

1) Please try the search box at the top of every page before you ask for help.

2) Try to post your question to the appropriate page.

3) Tell us everything we need to know to help such as the type of cooker and thermometer. Dial thermometers are often off by as much as 50°F so if you are not using a good digital thermometer we probably can’t help you with time and temp questions. Please read this article about thermometers.

4) If you are a member of the Pitmaster Club, your comments login is probably different.

5) Posts with links in them may not appear immediately.

Moderators